I’d be the first to admit I’m a music snob. Not that I think my tastes are better than anyone else, just that they are very particular. I like to think I have an informed opinion about the listening choices I make.

When I went to university, I was asked if I had any preferences about whom I shared student accommodation with. “No heavy metal freaks or jazz buffs”. I’ve still not changed my opinion of heavy metal, but my attitude towards jazz, like my appreciation for red wine, has only improved with age.

When I went to university, I was asked if I had any preferences about whom I shared student accommodation with. “No heavy metal freaks or jazz buffs”. I’ve still not changed my opinion of heavy metal, but my attitude towards jazz, like my appreciation for red wine, has only improved with age.

Not all, jazz, mind. Two words that strike dread in me are “gypsy jazz” – along with trad, dixieland and rag time, I find it most of it too fiddly, over-ornate, bordering on cheesiness. Similarly, for me, listening to “smooth” artists like Kenny G is akin to wading through treacle. There are certain instruments that I find very difficult to stomach in a jazz context – trombone, soprano saxophone, violin and acoustic guitar. And the big band sound is something I can only endure very selectively. Much of what is labelled fusion also leaves me cold, although I do make an exception for Soft Machine.

I suppose my point of entry is post bop, along with modal and free jazz. And while cool jazz can take itself far too seriously, at least it generally doesn’t fall into the trap of virtuosity for its own sake. (I’m always reminded of the criticism of Mozart attributed to Emperor Joseph II – “too many notes!” – when it comes to the noodly end of the jazz spectrum.)

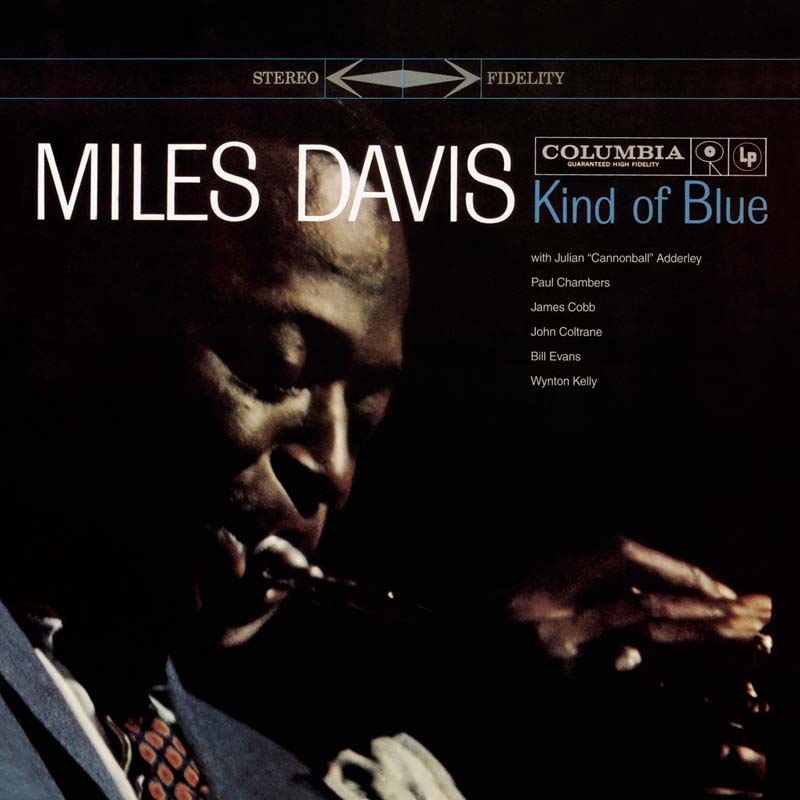

Like many people, one of my first real engagements with jazz was Miles Davis’s “Kind of Blue”. As a self-contained statement on “modern” jazz, it still astonishes with each listen. Despite its ubiquity, I never tire of hearing it. (In point of fact, the first Davis album I sought out was “In A Silent Way”, after it was used as a reference point in a review of A Certain Ratio’s debut album. Strange but true.) I’ve since come to appreciate the full canon of Davis’s work, although I have never warmed to his final records, recorded for the Warner Brothers label. His albums are often grouped into specific periods, rather like Picasso’s art, which only adds to his status and legacy.

At various times, my personal journey (and at specific stages in their careers) has encompassed Thelonious Monk, Modern Jazz Quartet, John Coltrane, Oscar Peterson, Ornette Coleman, Herbie Hancock, Pharoah Sanders, Alice Coltrane, Nina Simone, Stan Getz, Keith Jarrett, Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Ahmad Jamal, Mulatu Astatke, Sun Ra, Chet Baker, Antonio Carlos Jobim, McCoy Tyner, Eric Dolphy, Hank Mobley, Joe Henderson, Cecil Taylor, Marion Brown and Albert Ayler.

In terms of newer and contemporary artists, the only one who has managed to sustain my interest is Brad Mehldau, in particular his live solo performances – where he seems to have picked up from where Keith Jarrett left off in the 1990s.

And as I get older, I find that the only music radio station I can listen to is ABC Jazz….

Next week: Wholesale Investor’s Crypto Convention