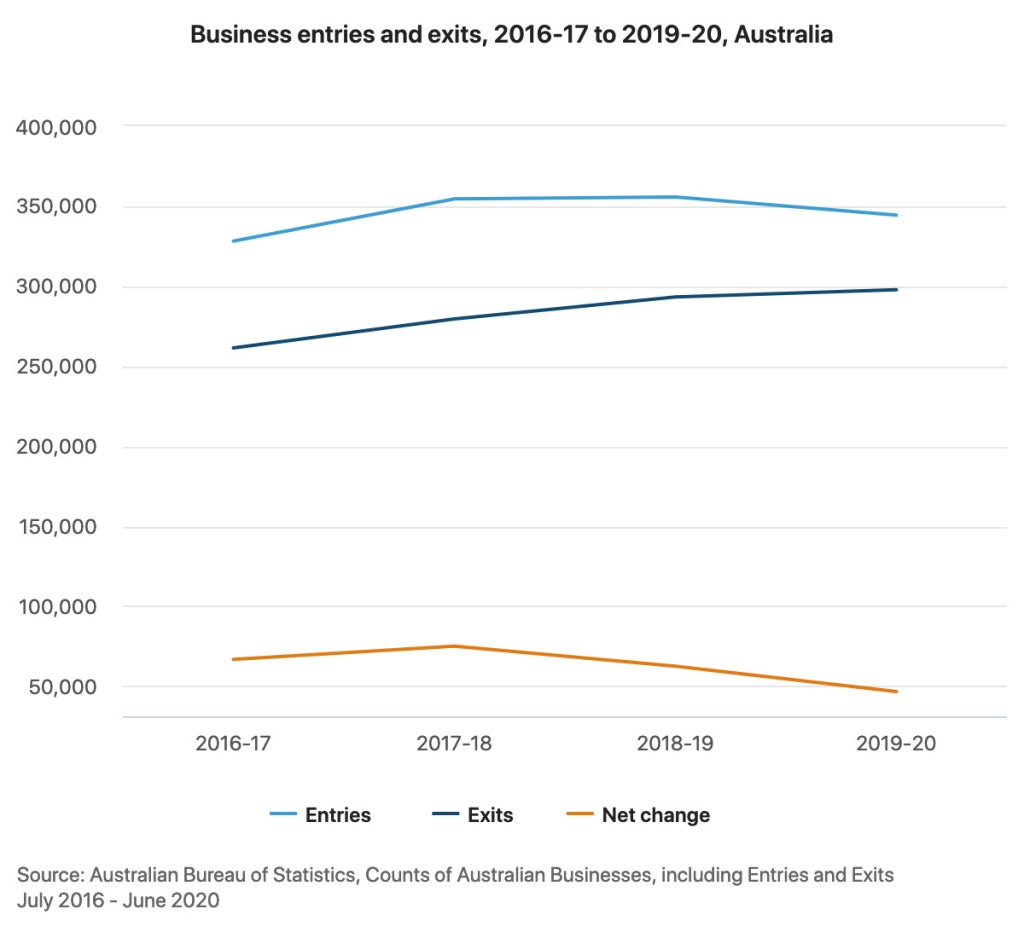

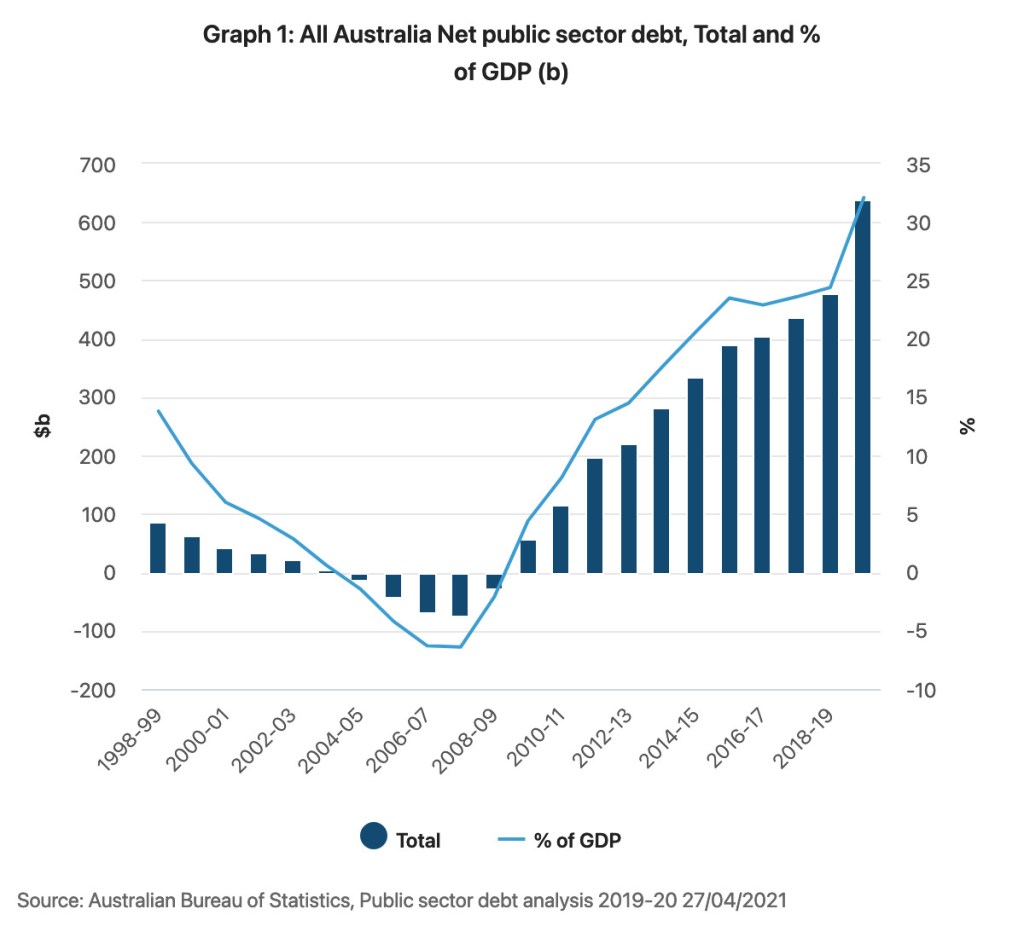

As the State of Victoria weighs up the costs of yet another lock down, you could be forgiven for thinking that the local economy has taken a further beating after the horrendous events of the past 15 months. Across Australia, thousands of companies and individuals accessed various government-sponsored financial aid packages to keep afloat, causing the federal government to borrow more money, at something like 8x the equivalent rate pre-COVID. National public debt is now expected to grow to more than 40% of GDP by the 2024-25 fiscal year – effectively double what it was in 2018-19.

So what has Australia done to retain its coveted AAA sovereign rating from Standard & Poor’s, and have the rating outlook upgraded from negative to stable? According to the ratings agency, and economists such as Westpac’s Bill Evans, there are probably three or four key factors that have warranted this optimistic economic reckoning.

First, while government borrowing (Quantitative Easing) has blown out as a proportion of GDP, the current low interest rates mean that the cost of servicing that debt is manageable.

Second, while the pursuit of QE has destroyed any hope of returning to an overall budget surplus, the deficit will return to similar levels last seen after the GFC, and the current account will continue to return a modest surplus over the coming quarters.

Third, despite the significant economic risks that were identified at the start of the COVID pandemic, the actual impact on the budget has been less than feared, and the economy is recovering faster than expected (as evidenced by latest employment data and consumer sentiment).

Fourth, Australian banks have seen an increase in customer deposits, meaning they are less reliant on more expensive overseas borrowing for their own funding.

Overall, just as with the GFC, Australia has managed to dodge a bullet (the shock to the system was less than anticipated) – in large part thanks to a resurgence in iron ore prices (again).

But weaknesses and disparities remain:

The over-reliance on commodity prices (mainly based on demand from China) hides the true nature of Australia’s balance of payments – we manufacture less than we used to, and our supply chains have been severely tested during the pandemic. And with international borders closed, we won’t see the same levels of GDP growth that resulted from immigration.

Our household savings rate as a percentage of disposable income has come down from its peak of 22% in July 2020, to less than 12% this past quarter, as people held on to their cash for a rainy day (or 3 months lock-down). The savings rate is expected to come down even further as consumers feel more confident and start spending again.

As with the GFC, home owners have chosen to pay down their mortgage debt – but the picture is more complex. Yes, interest rates remain low (and will likely stay so for at least another 18 months), despite commentary from another economist, Stephen Koukoulas suggesting that the RBA will have to raise rates sooner than expected. With property prices expected to increase 5-10% over the next 12 months, home owners will feel wealthier (but asset rich and cash poor?) as mortgage repayments reduce as a percentage of their home’s value. And while analysts at S&P expect banks’ credit loses to remain low while the economy recovers, the fact that two-thirds of banks’ exposures are to highly leveraged residential property could see increased stress when interest rates rise and if wage growth remains sluggish (more on the latter next week).

Australia’s sovereign credit rating is something of a badge of honour, and represents membership of an exclusive club – fewer than a dozen countries are rated AAA; no wonder it’s a big deal, and partly explains why the Prime Minister gets to attend the G7 (albeit as an observer). Comparatively speaking, Australia is doing very well when it comes to managing COVID (although we could be doing a lot better on a number of measures), and has an economy that continues to be the envy of many. Expect more on that AAA rating (“How good was that?”) as we head into the next Federal election…

Next week: Where is wage growth going to come from?