Following last week’s “compare & contrast” entry, another similar exercise this week, between artists Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, the subject of the NGV’s summer blockbuster exhibition.

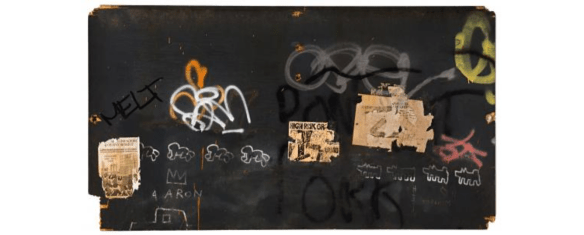

Keith Haring, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Other artists: “Untitled (Symphony No. 1)” c. 1980-83 [image sourced from NGV website]

Both died relatively young, and it’s as if they somehow knew they each had limited time, such is the intense pace at which they worked, as evidenced by their prolific output. If there is one element that really links them is their inner drive – they had to produce art, there was no choice for them, and they threw everything into it.

They each developed their own distinctive visual styles, much imitated and appropriated throughout popular culture, graphic design, video and advertising. Haring is known for his dog motif and cartoon-like figures, Basquiat for his iconic crown and text-based work. They also placed great emphasis on issues of identity, gender, sexuality and broader sociopolitical themes.

Where they perhaps differ is that Haring relied on more simplistic imagery (albeit loaded with meaning and context), using mainly primary colours, flat perspective (no shading or depth), and strong repetition. On the other hand, Basquiat’s paintings reveal confident mark-making, bold colour choices (not always successful), and an implied love of semiotics (even more so than Haring’s almost ubiquitous iconography).

Of course, we’ll never know how their respective work would have developed over the past 30 years – maybe what we now see is all there was ever going to be? As a consequence, there is perhaps a sense that they plowed a relatively narrow field, that they did not develop artistically once they became gallery artists. I’m not suggesting their work is shallow or one-dimensional (even though it can simply be viewed and appreciated “on the surface”), but it would have been interesting to see where their work took them.

Finally, we are still very close to the era in which they were active, and in that regard their true legacy will be in the influence they cast on late 20th century art and beyond.

Next week: Hicks vs Papapetrou