I’ve been working with content since I was a teenager – from writing articles for school magazines, to contributing gig reviews to a leading Manchester music magazine; from working for global media and information brands, to freelance editorial and writing projects.

Even now, as a business coach and consultant, I continue to focus on my clients’ content strategies – whether developing new products and services, managing IP, or capturing and commercialising in-house knowledge.

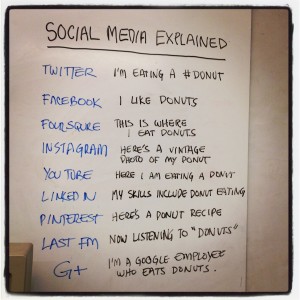

I have to admit to being an early sceptic about Social Media – but I soon recognised its importance, especially when building a personal brand on-line. Now it’s just another communication channel. I sometimes reflect on our ancestors who resisted the telephone, radio and television, and wonder if my own suspicions about Social Media will seem unfounded in retrospect.

About a year ago, I started this blog as a personal brand for my consulting work, as well as giving me a license to write about “Exploring the Information Age”, however tangential it might be to my professional work.*

After 12 months, I think I have found the essence to building a personal brand through social media – otherwise known as the AAA Guide to Blogging. Those elements are: Authenticity, Awareness and Attribution.

Authenticity

In an on-line environment where people hide behind avatars and aliases, you need to find the appropriate level of authenticity if you are going to be taken seriously by or establish trust with your audience. Being authentic means finding your “voice” to express yourself in any given situation, and to be true to yourself in that particular context.

I will admit to having several on-line profiles. For example, when connecting with my family and close friends, I am very circumspect about which Social Media platforms I use, and how I use them. My profile is extremely locked down and tightly controlled – you won’t be able to find me because I won’t let you in.

For my activities as a musician, I have another profile for self-promotion, sales and distribution, community engagement and beta testing new apps. You probably won’t find me because I use an alias, unless I am inviting you in.

Finally, in my professional life, I am very pro-active, interacting via an increasingly interconnected multi-channel strategy.

Does having multiple profiles mean I am being inauthentic? I would say no, because I am being authentic to who I am in those particular situations, and I don’t believe it is unreasonable to keep my private life, my personal interests, and my professional profile separate from one another. That’s why, even though I have a public profile on Facebook as part of my professional brand, I won’t be sharing my musical tastes because it’s not relevant (unless I might be going to a karaoke sessions with my clients?).

Awareness

Just as you need to be aware of the possibilities and limitations of different Social Media tools, you also need to understand your “character” when blogging, sharing and providing status updates. I see this as a natural extension to being authentic – in my professional life, should I really be sharing selfies (especially not at the client karaoke night…)?

There are 4 main categories of Social Media protagonists and bloggers:

1) Enthusiasts – personal stuff, “what I ate for breakfast”, no real purpose

beyond “sharing” or “look at me”

2) Broad Experts – know their Yammers from their Spammers, their Blogrolls from their Facebook Trolls – understand how and where they need to engage, they know what works for them (they have found their own level)

3) Niche Specialists – the Twitterati (Stephen Fry), the star fashion bloggers, the political and media pundits, viral cat videos, and the quirky (@God) – NOT Katy Perry – she probably has people to do that for her, namely….

4) Professionals – so-called “prosumers” who use Social Media as part of their job or about their work, or it’s part of their public and personal profile, and the boundaries are increasingly blurred.

Attribution

As far as possible, I always attribute third party content or references I use in my blogs, even if they are deemed to be in the public domain, and I endeavour to acknowledge the original sources as far as possible.

Not only can this create reciprocal links and traffic to my blog, I just believe it is more ethical, rather than “sharing” content with no attribution. It’s not just about copyright law, or respecting IP, I happen to think it is more intellectually honest to acknowledge original ideas, rather than imply they are our own.

I came across a good example recently on LinkedIn, where a connection “shared” an infographic on social media, without providing the original source. In fact, it almost looked as if it was an original post. However, I was sure I had seen the same content elsewhere, and after a short Internet search, I was able to locate the original post and the author very easily. Maybe it’s laziness, or lack of consideration, but this common failure to attribute sources risks undermining your work and devaluing your creativity.

Final thoughts on blogging and Social Media

• No-one gets it right 100% of the time – and even when we do, we don’t always know why

• Conversely, everyone gets it a little bit wrong, so the real learning is in that collective experience

• Prospective employers, clients, customers all expect to find evidence of your Social Media and online presence – even if you are only engaged in Social Media in a professional/work capacity, you still need to develop a personal profile

*See previous blog 10 Rules for Effective Blogging. I recently did some analysis of my blog traffic, to see where my readers are coming from. I don’t use Google Adwords, and I don’t have any paid-for SEO – so I rely on my WordPress stats:

- Nearly half of all traffic is coming from social networks

- One third comes from search engines (of which Google accounts for 90%)

- 10% comes from Reddit

Search results for my blog always come in the top 10 (plus it helps to have an unusual first and last name – always #1 search result!)

Footnote A slightly different version of this article was given as a presentation at the Australian chapter of PR over Coffee earlier this month