Whether or not we are comfortable with the notion, the work we do can come to define us. In some societies, family names are derived from our forebears’ occupations or professions (Butcher, Baker, Smith, Cartwright, etc.). The rapid shift to the knowledge economy is challenging our traditional economic relationship with work, and what it means to be an employer or employee. For example, the idea of a “job for life” within the same industry, let alone the same company, is no longer the norm.

“Welcome to the working week”

This past week I have been listening to the latest thinking on the nature of “work”, from the perspective of technology and its impact on task-based activity (courtesy of Donald Farmer from Qlik), and from the perspective of organizational culture and its importance in motivating knowledge workers (courtesy of Didier Elzinga of Culture Amp). If you are not familiar with either of these thought leaders, than I thoroughly recommend them to anyone interested in organisational behaviour, career development, business transformation and lifelong learning.

Technology and changing demographics require each of us to reframe our ideas about work as a homogenous lifelong activity, because the economic bargain between employer and employee is no longer as simple as a 40 hour working week and a regular paycheck.

Reframing “employment” #1:

By 2020, average job tenure will be 3 years, and around one-third of the workforce will be employed on a casual basis (part-time, temporary, contractor, freelance etc.). The proliferation of services such as Freelancer, O-desk/Elance, Sidekicker, 99designs, Envato and Fiverr are evidence of this shift from employee to supplier.

“The Dignity of Labour, Pts. 1-4”

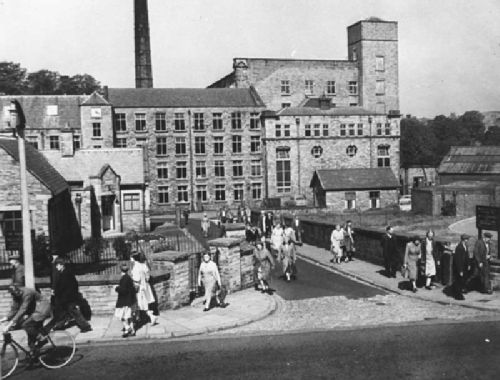

Around 200 years ago, at the height of the Industrial Revolution in England, the typical worker was employed in a factory or mill, lived in housing owned by the employer, and was paid some or all of his wages in the form of vouchers that could only be spent in shops also owned by the employer. A hundred years later, my grandparent’s generation were still exposed to the practices of indentured labour (“master and servant”) or the idea of “going into service” (as domestic workers). My father’s generation is certainly the last in my family to have had a 30-year salaried career within the same organisation.

So, in just a few generations we have transitioned from the idea that employment provides for all our needs, to the increasingly common perception that every worker is in fact a micro-business, supplying their labour to multiple employers or clients via fee-based services. (The potential irony here is that in a world of freelancers and contractors, the time-based or task-linked approach to employment pricing starts to resemble Marx’s idea of the labour theory of value…..).

“Cottage Industry”

It’s also interesting to note that before workers were employed in factories, and as agrarian labourers transitioned from toiling in the fields to working in manufacturing production, they were hired on piece-rates, working from home in the form of (literally) cottage industries. Of course, this was not exactly self-employment, as their tools (looms and lathes) were probably provided by their “client” who also set the prices (for raw materials and finished goods), had exclusive rights over the finished goods, and determined the number of units required. But, within the constraints of meeting target numbers and societal norms such as Sunday observance and customary holidays, these labourers were “free” to work for as many hours as they wanted, and at times that suited them. So, like many contemporary issues we still seem to be struggling with, flexible working arrangements are nothing new….

“Work is a four-letter-word”

Aside from connecting with your purpose, understanding your personal value proposition and knowing what you are “worth” in the market, one of the biggest challenges I see for employees/workers is the paradox between shorter careers (witness the increasing unemployment rates among older workers) and longer working lives.

Thanks to medical advances, we are living longer, but there is a mismatch between workforce participation rates and increased welfare and social security costs, leading to continuous policy tinkering on pensions, tax and superannuation.

As individuals, we need to build up sufficient financial assets to sustain us both post-retirement, and during erratic periods of personal income. As “free agents”, we have to learn to live with:

- increasing job insecurity (companies continuously de-layering and restructuring)

- significantly different career paths (compared to personal aspiration/expectation)

- rapidly changing working environments (hot-desking, co-working spaces)

- greater self-reliance (“bring your own device”) and

- heightened resilience (“shape up or ship out”)

“Opportunity”

The good news is that the model of portfolio, portmanteau and protean careers means that new jobs and new forms of working are emerging all the time – and with personal resilience etc., come flexibility, adaptability, knowledge sharing, skills transfer and new opportunities for personal development, along with self-defined roles, self-directed learning, self-managed performance and self-determined accountability.

We are no longer defined just by what we do, but how/where/why/when we do it.

Reframing “employment” #2:

A friend recently asked me for some advice on how to transition from “employment” to “self-employment”. She has regular part-time work with one organisation (which she views as employment), but wants to find more of her “own work” with other clients. She does not want to give up the part-time gig just yet, but feels that it is preventing her from growing her own business. So I suggested that she should see herself as being self-employed already, and that the part-time work is her first client, allowing her to build a portfolio of new business.

“Earn enough for us”

What does this brave new world of work mean for employers – in particular, what is the new economic bargain organisations need to have with their workers?

If companies are no longer willing/able to offer long-term, permanent employment opportunities, how do they manage their labour requirements, attract and retain the best talent (when they need it), and engage highly motivated and skilled people?

First and foremost, the idea of workplace flexibility has to be truly reciprocal – but obviously aligned and clearly articulated – to be of any real benefit to both parties.

Second, if employers are increasingly reliant on freelance resources, this does not obviate their obligations to invest in their workforce – whether that includes benefits, training or rewards and recognition – the same as they would have in their employees.

Third, companies will need to do an even better job of attracting and retaining the skills and knowledge they require – and be willing to offer different kinds of incentives (e.g., opportunities to work on engaging projects and to collaborate with interesting people) beyond basic pay and conditions.

Fourth, employers may have to adjust to the idea of “syndicating” their talent resources (“it’s the shared economy, stupid”) not just within their own workplaces, but across their client organisations, suppliers, service providers and other collaborators – sometimes, even their competitors. Employers can no longer expect to have a total monopoly on their workforce talents, unless they make it really interesting, financially or otherwise…

Fifth, if companies continue to espouse the message that “our people are our best asset” then they need to update their asset management model to demonstrate they mean what they say. For example, more needs to be done in helping employees to retrain and up-skill (for jobs and roles that haven’t yet been thought of), even if that may mean employees are more likely to move on. The amount of goodwill that this will create in the wider community cannot be underestimated.

Reframing “employment” #3:

Employers and HR managers are re-assessing how they evaluate employee contribution. It’s not simply a matter of how “hard” you work (e.g., the hours you put in, or the sales you make). Companies want to know what else you can do for them, how you collaborate, do you know how to ask for help, and are you willing to bring what you know to the role?

Finally, rather like their employees, employers are increasingly expected to connect with their purpose and to align their values with their objectives. New entrants to the workplace are better informed about the organisations they work for and want to work for, because free agents know they have a choice.

Next week: How to work with Boards