At the time of writing, Melbourne is poised to move out of Stage 4 lock-down – but don’t hold your breath in anticipation: we have become used to the drip feed of information, contradictory policy narratives, and the political process of softening up the public not to expect too much too soon.

Meanwhile, the Public Inquiry into the failure of the Hotel Quarantine Programme will this week feature three key political witnesses, namely the State Premier and his Ministers for Health and Jobs respectively. Based on the evidence given to the Inquiry so far, plus the Premier’s daily press briefings, it’s clear that no-one in public office or in a position of authority can say specifically who, how and when the decision was made to engage private security firms to implement the hotel quarantine arrangements.

Of itself, the decision to outsource the hotel security should not have been an issue – after all, the State Government engages private security firms all the time. However, it has now been established that nearly 100% of the community transmission of Covid19 during Victoria’s second wave of infections can be traced back to returning travellers who were in hotel quarantine. On top of that, the Inquiry has seen evidence of people breaching the terms of their quarantine, and has heard a litany of errors and mismanagement at every level of administration.

Although the Premier as leader of the Government has claimed overall responsibility for the quarantine debacle (and which led to him imposing the Stage 4 lock-down), it’s worrying that no-one in his administration (himself included) can recall the details of the fateful decision. Pending the outcome of the Inquiry (and the result of the next State Election), it remains to be seen whether the Premier or anyone else is actually going to be held directly accountable for the blatant quarantine failures.

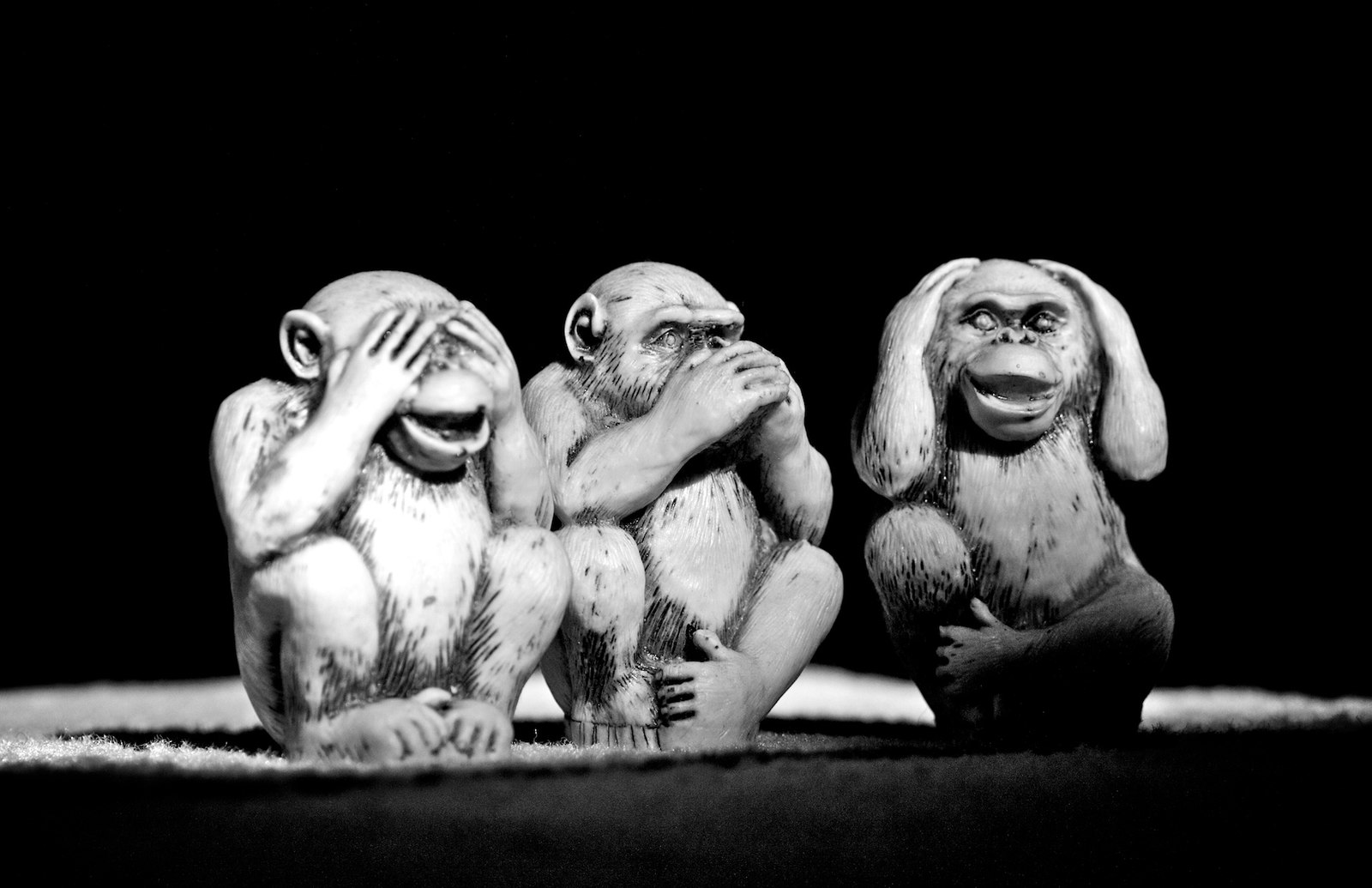

Not only that, but Ministers, their senior civil servants and key State Administrators all seem to be denying responsibility for making any concrete decisions on the hotel quarantine security arrangements, let alone to knowing who did, when or how. It’s like a bizarre remake of the Three Wise Monkeys, in triplicate: first, we have the Premier and his two key Ministers; then you have their respective Departmental Secretaries; finally there is the Chief Health Officer, the Chief Commissioner of Police and the Emergency Management Commissioner.

Instead of “see no evil, speak no evil, hear no evil” it’s more a case of: “I didn’t see who made the decision, I didn’t speak to anyone who made the decision, and I certainly didn’t hear from anyone who did make the decision“. In exchanges with the media and at the Inquiry, some of the players have even tried to deflect responsibility onto their counterparts, along the lines of, “I assumed X had made that decision”, or “the decision had been made before I got to the meeting”.

Yet, somehow, a decision was made.

So was the decision taken telepathically, organically or via a process of osmosis – the people involved simply “knew” or “sensed” that a decision had been made?

In case anyone think I am being unfair or I am deliberately misconstruing the situation, let’s follow the logic of what we are being told, and as a consequence, what we are being asked to believe. Earlier this month the Hotel Quarantine Inquiry heard evidence about an apparent administrative “decision” to exclude the Chief Health Officer “from taking control of the state’s coronavirus response against his wishes and in contradiction to the state’s own pandemic plan”.

A few weeks prior, the Premier was reported as saying:

“I wouldn’t want anyone to assume that anyone had made an active decision that [the Chief Health Officer] should be doing certain things.”

And there is the nub of the issue – as voters and tax payers, we are expected to believe that none of our elected representatives, civil servants or public officers have made specific decisions about key aspects of the public health response to the pandemic.

In his evidence to the Hotel Quarantine Inquiry, the Secretary to the Department of Premier and Cabinet gave further insight into the decision-making processes. Like his colleagues and counterparts, he was “unaware” who ultimately made the decision to use private security firms. Instead, he suggested that decision-making was shared among key experts:

“I have a strong view that the concept of collective governance where you’re bringing together the special skills of different actors to deal with complex problems is an important part of how we operate,” he said. “So you’ve asked for my response, as the head of the public service, I can see some legitimacy in the idea of there being collective governance around an area such as this.”

So does “collective governance” mean that no single person is responsible for decision-making (and as such, no individual can take the credit or be blamed for a specific decision)? Or does it mean that everyone involved is responsible, and as such they are all accountable for the decisions made by the “collective”, or which are made in their name or on their behalf? In which case, if the decision to engage private security firms was the root cause of the second wave and the Stage 4 lock-down (and all its consequential social and economic damage) should the “collective” all fall on their swords?

As the Guardian commented last week:

“The hearings have been running for several weeks now, and no one has yet claimed personal responsibility for the decision to use private security guards in hotel quarantine. The murkiness around this decision […] has become almost more significant than the decision [itself]. In inquiries like these, being unable to elicit a clear answer to such a key and really simple question is usually not a good indicator of the underlying governance protocols in place.”

Having once worked in the public sector for five years, I know that there are basically four types of decision-making outcomes in Public Administration:

- A good decision made well (due process was followed, and the outcome was positive and in accordance with reasonable expectations – job done)

- A poor decision made properly (the due process was followed, but unfortunately it turned out badly – shit happens)

- A good decision made poorly (we stuffed it up, but sometimes the end justifies the means – high-fives all round)

- A poor decision made poorly (no-one in their right minds would have come to that conclusion, and the results speak for themselves – we’re toast)

Subject to the evidence to be presented to the Inquiry this week (and depending on how the transition out of Stage 4 lock-down goes), I fear that in the case of the decision to outsource hotel quarantine security, it sits squarely in category #4.

I can almost imagine the scenario when the “decision” to hire private security guards was communicated to the various Ministers, Civil Servants and Public Officers:

Member of the Collective #1: “OK, the State Government has been asked to implement the Hotel Quarantine programme on behalf of the Commonwealth, so we need you, you and you to organise the security hiring arrangements. We don’t care how you do it, or who you use, but just get it done, and make sure that any poor outcomes can’t be attributed to any of us.”

Member of the Collective #2: “Can we take up the offer of assistance from the ADF?”

Member of the Collective #1: “Don’t ask. (Don’t get.)”

Member of the Collective #2: “Oh, so we’re working under a policy of plausible deniability?”

Member of the Collective #1: “You didn’t hear that from me.”

Member of the Collective #3: “Is so-and-so aware of this decision?”

Member of the Collective #1: “I don’t know, and you don’t need to know either.”

Member of the Collective #4: “Got it. Didn’t see it, didn’t say it, didn’t sort it.”

Of course, this dialogue is pure conjecture on my part, but I think we’ve all seen enough episodes of “Yes Minister”, “The Hollowmen” and “The Thick of It” to know how these things play out….

Next week: The Age of Responsibility