I ask the question because like many other users, I am holding off upgrading to iOS 7. I have even backed up a copy of iOS 6.1.3 to “freeze” it in case I am forced to upgrade before I am ready. I am holding out until some of the potential glitches and bugs are ironed out. I was first alerted to the issue by the developers of Audiobus, but it seems that they are not alone….

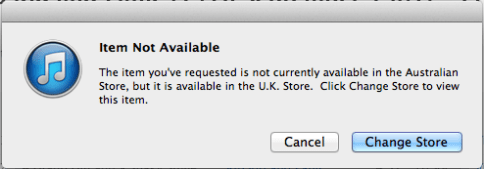

Leaving aside the fact that many customers could not easily download the new operating system, or the fact that the shiny “new” iTunes Radio is not available outside the US, it seems that iOS 7 has been launched rather hastily, along with iTunes 11.1 (barely a month after iTunes 11.0.5….).

Audiobus had earlier notified their customers that iOS 7 would automatically update apps, without users even knowing, which risked corrupting personalised settings, especially for more complex apps. Now, it seems that the upgrade function has been modified, so that users can select when and how their apps will be upgraded.

But Audiobus, who launched inter-app connectivity for live audio, could be one of a number of apps that Apple is seeking to render obsolete or redundant, since iOS 7 supports Inter-App Audio. Other apps seemingly under threat include those featuring, photography, music streaming and document sharing.

Even an app that utilises the amount of contact area made by your fingers on the device touch screen was forced to remove that functionality by Apple. To me, this type of gesture or articulation could be critical in helping people with accessibility issues – so why should its deployment be restricted at the whim of Apple, rather than being made available to all developers?

Apple will not countenance any app that “interferes” with the telephony functions of an iPhone, and until iOS 6 introduced “Do Not Disturb”, I wonder how many 3rd party apps with similar functionality were rejected by the iTunes Store?

Now Apple appears to be cornering other functionality and interactivity design – even if Apple didn’t think of them first…. In fact, every original app design or feature is like a piece of middleware, that allows the user to interact with the device’s operating system, in a way that the system developers probably had not anticipated; this process is at the heart of innovation – taking something good and making it even better.

The fanfare of the new iPhone 5S (and its colourful cousin the 5C) probably won’t allow any criticisms about iOS 7 to rain on Apple’s new product parade – but I can’t help feeling that as customers we are being oversold each new release of an Apple device or operating system upgrade.

Although every incremental release or upgrade is supposed to come with lots of great new features and benefits, we actually lose some functionality and user options as Apple continuously locks down customisation and personalization. For example, iTunes 10.8 disabled the option to manually sync Notes between devices – now it’s all done via iCloud, and legacy data that predates iCloud (or is in a folder “On My iPhone” and thus not “recognised” by iCloud) has to be copied over to a cloud-enabled folder, one-by-one, as I have learned to my cost. Why does Apple think it can determine how I manage my own data?

While I understand that all product developers rely on user experience and expectations to help them develop new features, and they need customers to migrate to single, common platforms and versions as quickly as possible post-release, I’d prefer that my loyalty and patience were not taken for granted.