At some point in your career, you will find yourself working with Boards. In particular, if you are appointed to a CEO role, or if you are part of an executive team, there is an expectation or requirement that you will attend regular Board meetings, and you will need to develop the necessary skills and expertise to navigate the process.

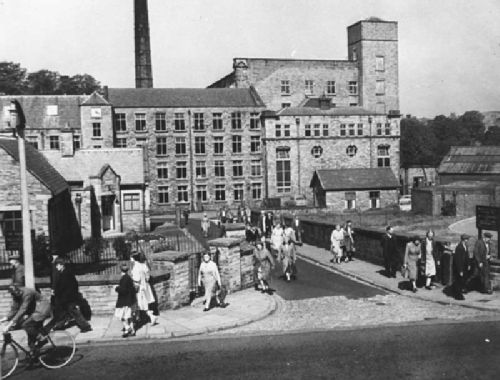

Board meetings don’t have to be as daunting as this… (The SPECTRE hierarchy as portrayed in “Thunderball”)

The following comments were crowdsourced from a group of senior executives and non-executive directors who were asked to share their views on how someone in a senior management role should prepare prior to presenting at a Board meeting – in particular, where there may have been a change of Chairman, a new CEO or new appointments to the Board. It’s designed to be part “how to” guide, part coaching tool, and part insight drawn from actual experience – and in some cases, the comments answer the question “what I wish I’d known before I stepped into the Board meeting…”.

The comments have been divided into three sections:

- Governance

- Relationship between the Chairman and CEO

- Presenting to Boards

1. Governance

How are Board meetings run?

1) From experience, working with a Board really depends on how the Chairman likes to run things. The Chairman is usually assisted by the Company Secretary (or a Secretariat), or other legal officer of the organisation, who may also form part of the senior management team.

2) The Secretary is responsible for making sure everything runs smoothly for the Board members. In addition to supporting the Chairman, the Secretary schedules the Board meeting, circulates the relevant notices and papers in advance, prepares the meeting agenda, and records the minutes. (In some organisations the CEO will be as involved in preparing for a Board meeting as the Secretary.) The Secretary will also assist the Chairman in ensuring the meeting is conducted in an orderly fashion, and in accordance with the company constitution and any other rules governing meetings.

3) If you have been asked to attend a Board meeting to report on an important project or to present a new initiative, it should be noted in the agenda. Depending upon protocol, you may only be invited into the room at the designated point in the agenda. You may find that you don’t have a vote at the meeting (and in general, your voice should only be heard when your contribution is actively invited!) and you may be asked to leave again before a formal vote is taken.

4) A good Chairman will invite comments from all attendees at the Board meeting, especially where external or specific expertise is being sought. Although other Board members will want to ask questions of senior managers and anyone else presenting, it will depend on etiquette, and they may need to direct these questions via the Chairman.

Board Induction

5) The CEO and the executive team can help the Chairman in the induction of new Board members, something that the Secretary should be able to facilitate. For new Directors, it may not be easy to understand the organisation, or what is expected of them, or what their contribution should be.

6) The transition will be harder for Board members coming from the private sector into the government sector, or vice versa. A Board Induction Manual is an invaluable tool for a new Board member to familiarise themselves with the organisation. The CEO should also ask their managers to stand in the Directors’ shoes for a minute to work out what the new Board member may need (and not assume they already have everything they require.)

7) If a relationship can be built through the induction process, then it should be easier to understand where new Board members are coming from, identify their key areas of knowledge or expertise, know what their risk appetite is and anticipate where their interests will lie.

Board Renewal – managing change

8) Most Board members are elected or appointed for fixed terms, ensuring that there is a renewal process. In some cases, there will be a full spill, and the formation of a totally new Board.

9) One of the understandable traps that the CEO and management team may fall into is assuming they have to maintain the status quo – which may or may not meet the needs and expectations of the new Chairman and a new or significantly changed Board.

10) In those circumstances, the CEO and Chairman should sit down in advance and set out their respective expectations/needs/preferences, including an early feedback process soon after the first few meetings to get things off to a firm footing and to avoid any festering dissatisfaction.

2. The relationship between Chairman and CEO

Boards vs Management

11) The pivotal connection between a Board and the Management team is the relationship between the Chairman and CEO. There has to be a level of trust, rapport and mutual respect, otherwise the organisation risks being dysfunctional.

12) A common view is that Boards are expected to be “eyes on, hands off” – that is, they are there to view what is going on, but not to get involved with operational matters which are the responsibility of Management.

13) Equally, the Board is responsible for setting and directing the overall strategy, and holding the CEO and executive team accountable for achieving the agreed objectives.

Who can help you?

14) The CEO has a key role in facilitating the interaction between the Board and senior managers. If you don’t have direct access to the CEO in advance, then find out if your own manager or another member of the senior executive team can help forge an introduction. While the term “patronage” might seem outdated, your attendance at and participation in the Board meeting will usually depend on someone advocating on your behalf, or lobbying for you to be there in person.

15) If managers are attending a Board meeting to present or speak on a particular topic, then this should be noted in the agenda or notice of meeting. The CEO will also need to work with managers to ensure they are prepared and “worded up” on what they will be presenting. Getting the balance right between reporting facts, offering opinions, making a recommendation or seeking a decision is important, especially on a packed agenda!

16) As mentioned above, the role of Secretary is also very important in getting people prepared to engage with the Board – not just deciding the agenda but also briefing presenters on what to expect, and ensuring papers are not too long, cover the issues and have clear recommendations for a decision.

17) The Secretary also wields considerable influence as they get to minute the decision (which is not always as clear as it should be). Managers who are not Board members should receive a copy of the relevant minutes of any meeting they have attended.

Lobbying and briefings in advance

18) For some big issues you may be asked to present on, briefing and lobbying often happens outside of the Board meeting. You shouldn’t assume that a Board will make a good decision when all they get is a Board paper and a few days’ notice – especially around complex issues. Offering advance briefings to Board members (especially new directors) can help them get up to speed on major issues.

19) Even though your item is on the agenda, you should assume that the meeting will not have sufficient time to allow a full presentation or discussion of the issues. Hence the importance of advance briefings, especially where you are seeking a decision based on your recommendation.

3. Presenting to the Board

Why are you there?

20) Maybe you’ve been asked to make a presentation on a new strategic initiative, or to provide an update on a major project. Or perhaps it’s part of a regular program where managers and team leaders get to interact with the Board members. Whatever the case, you should establish in advance why you have been invited to attend, as this will frame the context for your contribution to the meeting.

Preparation, Preparation, Preparation

21) As with any presentation or public speaking, be comfortable with your material and try to know your audience in advance. Find out who will be attending, and if possible, identify if they have previously expressed any views on the topic under discussion. Equally, Board members should be provided with a brief bio of new managers presenting at the meeting, especially if it’s their first time to attend.

22) If you have also had an opportunity to provide Board members with an advance briefing, the preparation will help you to focus on the important and critical information, so you can establish the level of knowledge in the room and make sure the discussion does not waste valuable time going over the known facts or revisiting agreed positions.

23) While your expertise will be sought, more importantly, if you are seeking a decision of the Board, it is essential to be clear about the decision relates to, and you should offer a specific recommendation or preferred course of action.

Protocols and Etiquette

24) As mentioned above, Board meetings will be conducted in accordance with the constitution or other rules of the organisation. Meetings will also follow the Chairman’s preferences, with the support of the Company Secretary.

25) There are some basic “Do’s and Don’ts” you should consider, especially if you are attending or presenting for the first time:

- Board members are not your friend – they have a governance role to perform

- The CEO owns the relationship with the Board, and must know and in most cases approve all interactions between Board members and managers (as a manager, you should notify the CEO of any unsolicited approaches you receive from Directors, or in exceptional circumstances, you should notify the Chairman)

- In the meeting, the Chairman of the Board (or Sub-committee meeting) is usually addressed as Mr Chairman or Madam Chair (but check with the CEO or Company Secretary in advance!)

- Boards require a structured agenda, well-thought out papers, clear recommendations, proper minutes and agreed actions or decisions (make sure you are clear about what you are asking for)

- Board meetings are formal affairs, and while social banter is fine before and after the meeting, keep it business-like during the meeting itself

26) The Australian Institute of Company Directors, the Governance Institute of Australia, other professional bodies as well as NFP organisations (e.g., Leadership Victoria) often run courses and publish articles on these topics.

Learning experience

27) Whether you are General Manager reporting to a Committee of Management or a team leader presenting to senior executives, these comments should provide are some useful ground rules for how to prepare, what to expect, and how to conduct yourself at those meetings. In any event, the experience should be seen as a learning opportunity, and a chance to gain some professional exposure – but it’s not a license to show-off or grandstand!

Note:

This article incorporates comments from my former colleagues Fabienne Michaux, Marianne Matin, Louise Griffiths and Carol Benson, who were each contributing in a personal capacity.

Next week: Digital Adaptors